Text by MARIA VITTORIA BARAVELLI

È la fine degli anni Settanta, anni tumultuosi per la politica, l’arte, la vita, e una giovanissima ragazza americana trascorre un anno a Roma per frequentare un corso avanzato di fotografia. Francesca Woodman studia e sperimenta le regole del ritratto e dell’autoritratto, inquadra e rappresenta il proprio corpo come soggetto e oggetto, facendo sua tutta l’eredità del surrealismo, della politica di quegli anni e della giovinezza, che ogni cosa esige e brama.

Nella capitale italiana trova la vita, la bellezza e la decadenza, ingredienti di un materiale magmatico, incandescente e chiaroscurale che si unisce in un flusso torbido e misterioso, fatto di nebbia e di spettri.

La finitezza del corpo e l’eternità dell’aura, il corpo che diventa una soglia aperta verso i misteri celesti. Una ricerca profonda come l’oceano e inconoscibile come lo spazio, arte concettuale e sensibilità poetica che saranno davvero la matrice del suo lavoro, breve, ma fondamentale per fotografi contemporanei e successivi.

È il gennaio del 1981 quando, appena rientrata in America, a soli 23 anni, decide di lasciarsi cadere nel vuoto dal ventiduesimo piano di un palazzo di Manhattan. Leggera, inesorabile, come un albatro candido e sensualissimo che nessuno è riuscito a salvare.

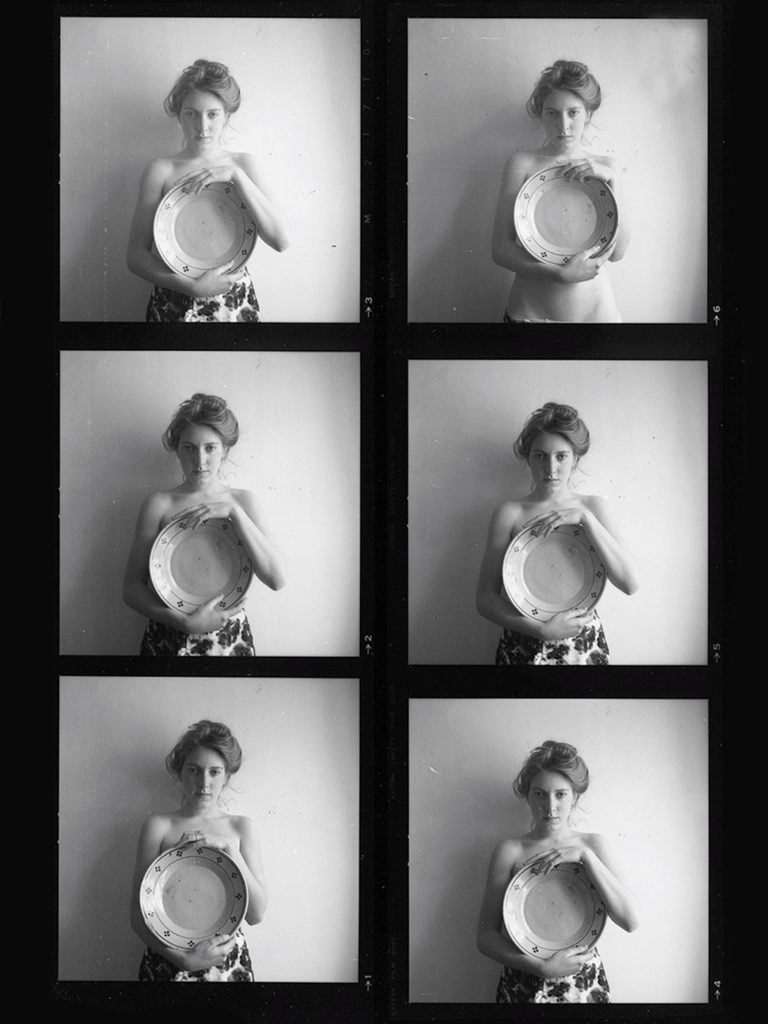

Ci lascia un corpus fatto quasi esclusivamente di fotografie auto-rappresentative, per la maggior parte in bianco e nero, scatti in cui Francesca Woodman si è ritratta nuda, vestita, mezza morta, strisciante, torbida e cristallina. Con una unica eccezione. Prima di tornare in America, a Roma, conosce un professore, a cui per un breve periodo lascia persino il suo appartamento in Via Dei Coronari. Non sappiamo esattamente il perché, ma Francesca con lui si sente a suo agio, al punto da decidere di lasciarsi fotografare. Da quell’esperienza nasce un ritratto sobrio, dolce, dall’acconciatura antica e uno sguardo da Maddalena, con un piatto in mano che mi piace pensare sia uno scudo involontario con cui forse voleva proteggersi.

Nulla dovrebbe essere più fedele di un autoritratto, un soggetto che si mostra e per noi diventa oggetto, ma quel professore, fotografo e amico di Francesca, che l’ha fotografata in un modo apparentemente semplice ma più visibile, Stephan Brigidi, ci ricorda una profonda verità. Forse di fronte agli altri siamo molto più nudi di quando ci guardiamo da soli. E allora forse è vero che la verità e la rappresentazione, la verità e la finzione hanno confini labili e confusi, ed esistiamo soprattutto attraverso gli occhi degli altri.

Nel tentativo di indagare, riscoprire e, anche solo per poco, riportare in vita questa figura di donna così inafferrabile, a marzo 2024 esce in libreria Francesca Woodman di Bertrand Schefer, edito da Joha & Levi.

“Woman With Large Plate” Roma 1978 photography Stephan Brigidi

English version

It’s the late seventies, tumultuous years for politics, art, life, and a very young American girl spends a year in Rome attending an advanced photography course. Francesca Woodman studies and experiments with the rules of portraiture and self-portraiture, frames and represents her own body as both subject and object, embracing the entire legacy of surrealism, the politics of those years, and youth, which demands and craves everything.

In the Italian capital, she finds life, beauty, and decay, ingredients of a magmatic, incandescent, chiaroscural material that merges into a turbid and mysterious flow, made of fog and specters.

The finiteness of the body and the eternity of the aura, the body becoming an open threshold to celestial mysteries. A search as deep as the ocean and unknowable as space, conceptual art and poetic sensibility that will indeed be the matrix of her work, brief but fundamental for contemporary and subsequent photographers.

It’s January 1981 when, just returned to America at the age of 23, she decides to let herself fall into the void from the twenty-second floor of a building in Manhattan. Light, relentless, like a candid and highly sensual albatross that no one managed to save.

She leaves behind a corpus consisting almost exclusively of self-representative photographs, mostly in black and white, shots in which Francesca Woodman portrayed herself naked, dressed, half-dead, crawling, turbid, and crystalline. With one exception. Before returning to America, in Rome, she meets a professor, to whom she even temporarily leaves her apartment on Via Dei Coronari. We don’t know exactly why, but Francesca feels comfortable with him, to the point of deciding to let herself be photographed. From that experience comes a sober, sweet portrait, with an ancient hairstyle and a gaze reminiscent of Mary Magdalene, holding a plate in her hand, which I like to think of as an involuntary shield with which she perhaps wanted to protect herself.

Nothing should be more faithful than a self-portrait, a subject that reveals itself and becomes an object for us, but that professor, photographer, and friend of Francesca, who photographed her in an apparently simple but more visible way, Stephan Brigidi, reminds us of a profound truth. Perhaps in front of others, we are much more naked than when we look at ourselves alone. And so perhaps it is true that truth and representation, truth and fiction, have blurred and confused boundaries, and we exist primarily through the eyes of others.

In an attempt to investigate, rediscover, and even just for a little while, bring back to life this elusive figure of a woman, in March 2024, “Francesca Woodman” by Bertrand Schefer was released in bookstores, published by Johan & Levi.