In June 2014 the “Islamic State” managed to occupy in a sort of blitzkrieg a large territory and its principle cities in the Sunni Arab strongholds of Syria and Iraq which they renamed the “Caliphate”.

From a media point of view, the valorization of the results is expressed in a youthful and highly visual language. Before the declaration of the Caliphate, when, in a surprise move, the Iraqi and al Sham ISIS succeeded in taking control of vast areas of Iraq, including the cities of Mosul, Tikrit and Samara, jihadist self-esteem grew enormously as did their conviction that they were the chosen few destined to do God’s will according to prophetic conduct.

This was communicated through social platforms and a more modern use of Twitter by their supporters who took up the themes, format and stories of typical Hollywood films in order to describe what, according to them, was happening in the field. Some pro-ISIS Twitter users – part of an English speaking cluster group of supporters- quickly re-designed posters for the film “300” in support of the victorious “800” Mujahedeen of the “Islamic State”. (They even quoted the Guardian as their source)

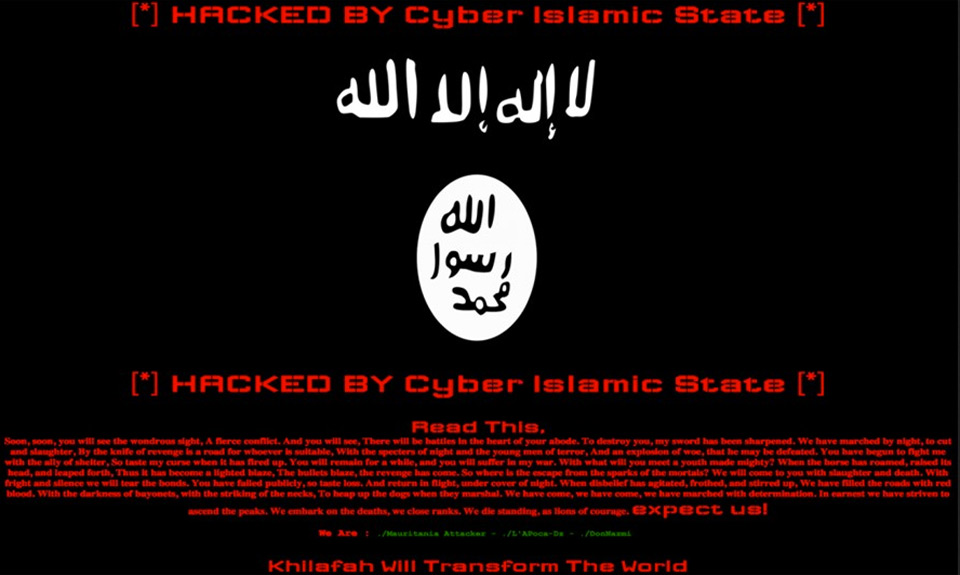

Not only do these fans and converts create content and share other users’ content, they also have a good understanding of the films and popular codes used within specific social groups. As a result they have created a message expressed through a peculiar link between mainstream Mujahedeen iconography and popular global culture dominated by elements from Westerns and other specific films. This mechanism of broadcasting on and offline worlds together is perhaps the most dangerous modern use of internet by jihadist activists in their aim to develop a movement rooted in the Middle East and North Africa.

At the same time, within the “state” and the “provinces” occupied by ISIS, Internet is the main means of communication with the outside world and is used to muster the support of Muslims everywhere and, in the best case scenario, to convince them to join this endeavor.

The overall picture, therefore, is made up of an ISIS which conquers part of Iraq and declares the Caliphate, integrated media activists on the front line with their global support networks and the media mujahedeen who publicize

their successes in HD videos and posters, images and language in Hollywood style distributed through social networks and social media.

In such a scenario, the diplomatic and cultural organizations which seek to contrast this kind of violent extremism need strategies based on network concepts to do so effectively.

Since jihadist subculture is characterized by a concept of personal participation, user generated content encourages and sustains ISIS propaganda. Consequently, such user generated content must not be underestimated.

While some users have a preference for shocking videos or “front line” films, others are more attracted by the civil side of the “state” where ISIS is presented as a functioning state supplying the population with energy, water, re-opened grocery stores or the fire brigade at Raqqa. Images of this kind allow ISIS to proclaim their superiority to the Sunni population and portray the “soft side” of the terrorist group by appearing to be saviors helping their brothers and sisters in their time of need.

ISIS cyberwar/3